Skip's Furry Dragon, Part 1:

The Importance of Dragonfly Nymph Imitations in Trout Lakes

In this section, Skip's Furry Dragon, Part 1, fly fishing author and master fly tier

Skip Morris describes the behavior and importance of

dragonfly nymphs when

fishing for trout in lakes.

In Part 2, he describes in clear and simple detail how to tie this highly effective

and life-like fly.

In Part 3, Skip shows you a simplified version of the tying steps for an easier way to

tie the Furry Dragon.

Damsels and Dragons

Skip's Furry Dragon

Skip's Furry Dragon

Perhaps because they are preoccupied with the frenzied spring-summer hatching migrations of plentiful wiggle-swimming damselfly nymphs, lake fly fishers tend to undervalue the sparse, quiet hatching of the dragonfly.

The damselfly and dragonfly are related (both belong to the order Odonata, though they are at once both strangely similar and different) which may

explain why they hatch at about the same time of year.

So because they are in fairly direct competition for anglers' attention, one tends to overshadow the other; which means the plentiful damsel overshadows the

scattered dragon.

It's different with trout.

Consider how they see the dragon nymph—big, corpulent, and frequently out and exposed on its own hunting sorties.

The trout, simply put,

see the dragonfly nymph as a standard and worthwhile prey.

Yes, the damselfly nymph can be of supreme importance to the lake fisher during its hatching, but day in, day out, its the nymph of the dragonfly that trout seek and find and that, day in, day out, fly fishers should concentrate on.

The Lake Dragons:

Aeschnidae and Libellulidae

There are two species of dragonfly of primary concern to the lake fly fisher: Aeschnidae, often called the "Green Darner," and Libellulidae,

often incorrectly called Gomphus.

Though Gomphus strongly resembles its close cousin, it's preference for slow currents makes it uninterested in lakes; Libellulidae, however,

prefers still waters—a true lake dragon.

You needn't know all the quirks of each species' character and design.

But what you do need to know is that these two dragons differ in the essential characteristics of size and behavior, and that one species or the

other may be numerous in some lakes while the other is scarce.

So knowing each a little is worth the effort.

Libellulidae Dragonfly Nymphs

This is the more patient, least-active of the two.

Camouflaged in silt or water plants it may move about quietly or simply wait for victims to come too near for their own survival; then it strikes fast,

jetting water from its abdomen, darting to its prey.

Consequently, imitations are usually best fished slowly, or with long pauses between long, quick strips of the line.

Expect Libellulidae to be most abundant on silty lake beds.

Some fly fishers actually let an imitation drop right down onto the muck; they then give it a little cloudy twitch now and then. The trout scoop it

right off the bottom, just as they do real Libellulidae nymphs.

Libellulidae is smaller than Aeshnidae, but this, of course, is relative—the nymph of the former may be a full inch long,

thick and corpulent, with much more meat to offer a trout than almost any mayfly nymph or caddis pupa could.

Libellulilidae, therefore, is hardly what you'd describe as small; think of it as being on the low end of very large for a trout-lake insect.

With its long slender legs and oval abdomen Libellulidae resembles a spider. At least it does when viewed from the top—its flattened abdomen kills the impression when the insect is viewed from the side. It's coloring is tan and brown, usually, but I've seen it in all pale-green. Nothing unusual about an insect species varying in color.

Aeshnidae Dragonfly Nymphs

If Libellulidae lies on the low end for a big insect trout regularly eat, Aeshnidae lies right at the very height because its nymph can

be over two thick inches long.

Many refer to Aeshnidae as the green darner—"green" for its most commonly predominant color and "darner" for absolutely no sane reason,

since "darning" is sewing up holes in cloth—the "green sock-mender."

I don't get it, but there it is.

The darner is generally the more active of the two primary dragon nymphs, out hunting to satisfy the hunger of its great body, rather than lying in wait like Libellulidae.

So imitations are sometimes best fished fast, suggesting the swift pulsing swim of the nymph on the attack or in retreat.

But the darner nymph usually crawls and swims quietly about while conducting its business between ambushes, so an imitation fished slowly is the norm. I often mix the fast with the slow in retrieving my nymph, believing that the natural mixes them too.

Dark-green is it's main color, with mottled brown and a rough, broken black stripe down its back. The darner isn't so broad and ovoid in the abdomen as Libellulidae, but so much longer and deep there that the result is an abdomen that is really thick. This, combined with noticeably shorter legs in relation to the abdomen keep the darner from Libellulidae's spider-look.

Lines, Leaders, Tactics,

and How Deep to Fish the Dragons

Lines

My favorite line for fishing dragon nymphs is the full-sinking type II—but, as my fishing companions will tell you, that's my favorite line for trout

lakes in general, so my choice here will be no surprise to them.

For particularly deep water or a fast retrieve I may use a type III; for shallow water, a type I or,

occasionally, even a full-floating line.

Leaders

The subject of leaders for sinking lines always inspires lively debate. Let them debate; I like one around ten feet. Many prefer shorter leaders for this business,

but I feel better putting some invisible distance between line and fly.

Still, a ten-footer provides me with good control and plenty of sensitivity.

Using Anchors Around Shoals and Drop-offs

I like to drop anchor, then make a long cast across good water—a shoal or drop-off, usually. I count as the line sinks—"One-one-thousand, two-one-thousand,

three..." That's how I count, but almost anything that's consistent works. Then I begin the retrieve.

The thing is to figure out what count gets and keeps the fly close to the bottom but not so close as to snag. It's simple enough to determine: keep making longer

and longer counts until you snag a bit of plant or wood, then back up a little on the counting.

Trolling

Of course, there's always trolling, rowing or finning lazily along with lots of type-III or type-IV line out. It works.

Where to Find the Dragons

Dragon nymphs live in water from only inches up to around 25-feet deep. During non-hatching times, depths of around six to 20 feet are a good range for an imitation nymph.

During the hatch, search different depths to find the greatest concentrations of migrating nymphs—usually it's modest depths early, shallower late.

The nymphs creep quietly along the bottom, shore-ward. Near the lake's edge they climb out on trees and rocks and upright plants and up onto shore to split

their outer husk and unfurl wings for flight.

Dragonfly Hatches

Hatching usually begins in mid-morning and continues through the day. This is no easy abundance, like a hatch of mayflies or damselflies can be—immature insects out in open water—it's a scattering of creeping half-hidden quick-swimming nymphs with good evasive tactics.

But they are big nymphs, somewhat concentrated—really big nymphs. So don't expect clouds of insects and wildly feeding trout; expect a modest number of quiet nymphs to creep from the water and hatch, and expect the possibility of steady fishing, with fast fishing an unlikely but not impossible prospect.

Dragonfly Nymphs and Some Popular Imitations

There is no shortage of effective dragon-nymph fly patterns.

They run the range from simple—the Carey Special; to complex—Darrel Martin's Woven Dragonfly Nymph; with all sorts in between.

I've fished the Carey and Darrel's fly and have taken fine trout on both. A buoyant foam pattern of my own—the Skip's Predator—rises above

lake-bed snags and is especially good for trolling.

One could select freely from among the many established dragon-nymph imitations and have a productive fly.

So I'll make no extravagant claims for my own Skip's Furry Dragon; I'll just tell you what it does, and why, and how I came to it.

Then it's yours to decide if you want to tie it and try it.

But I'll tell you this: It has become my first choice for a sunken lake fly and has

taken a great many trout for me from a great many lakes over the past few years.

The Trials and Tribulations of

Developing the Skip's Furry Dragon

When fishing lakes, I have lost too many trout on long-shank hooks—that's my belief.

I have also landed a great many trout on long-shanks...but not so many as on standard-shank and even short-shank hooks. The Skip's Furry Dragon can be

tied on either of these last two, but it's designed to avoid the first.

This, of course, means a fly with an extended body. The extended body, in my mind, is either good or bad—good if it's soft and pliant, bad if it's stiff.

My belief is that the stiff extension interferes with sinking the hook-point.

The extension on this fly is composed entirely of fur—soft and pliant indeed.

Understand, please, that I have and still do use long-shank hooks in lakes; it's just a matter of preference—I prefer standard and short shanks,

feel they have a small but significant advantage over the long shanks, and use them instead of the long shanks when I can.

As far as stiff, extended bodies on flies go, I always try to avoid them, especially if the extension is long.

Imitating Reality...

Choosing Materials that Show Life

An Abdomen of Fur

A real dragon nymph swims in little pulses from the jetting of water out of its abdomen. The abdomen swells and contracts with each tiny spurt. The fur abdomen of the Skip's Furry Dragon swells and contracts in much the same manner.

Pheasant-Tail-Tip Legs

Additionally, the legs of real dragon nymphs sweep back hard with each shot from the abdomen, sweep back slightly when the shots are light during slow swimming, and wave about as the nymph crawls—simply put, the legs are often active. The pliant outstretched pheasant-tail-tip legs of the Skip's Furry Dragon wave with the fly's every twitch, flick to its sides with its every quick dart.

Eyes of Vernile or Ultra-Chenile

The eyes? They are supple and plausible. Supple because, like a supple extended body, they leave the hook free to turn into the jaws; plausible for the obvious reason.

An Inspired Design of Rabbit Fur

The Skip's Furry Dragon is partly borrowed, partly original, and partly in question as to which. The abdomen of varied colors of fur was inspired by Hal Janssen's Janssen Dragon. Hal makes his fly with trimmed marabou bound along the hook-shank; mine is rabbit fur, no trimming, extending well beyond the hook-shank.

The eyes on the Skip's Furry Dragon probably came from some other fly I saw somewhere, but I can't now be certain they are not my original idea.

The wing-case-legs, formed as they are on my fly, are to the best of my knowledge original.

Pheasant Tail for a Wing-Case-and-Legs Combination

The combination wing case and legs formed of a single section of pheasant tail makes a perfectly good wing case, and the legs I especially like (as, it appears, do the trout). They do require a bit of care, however, in being returned to the fly box—the fly must be mounted so the legs are free and out from the body, in their original position, otherwise they become matted and flat and later fail to bounce and flex on the retrieve.

It's this wing-case-legs combination that may challenge some beginning tiers. But it's an unusual and useful tying approach; I suggest you learn it. It's really more unconventional than difficult.

So, in this article, Skip's Furry Dragon, Part 1, fly fishing author and master fly tier

Skip Morris describes the behavior and importance of

dragonfly nymphs when

fishing for trout in lakes.

In Part 2, he'll describe in clear and simple detail how to tie this highly effective

and life-like fly.

Then in Part 3, Skip shows you a simplified version of the tying steps for an

easy way to tie the Furry Dragon.

Click here to hear Skip's interviews on popular podcasts...

*Announcements*

Skip has an essay in Big Sky Journal's annual Fly Fishing issue, called "Montana Hoppers: the Princess and the Brute" released February 1, 2023. Skip rewrote it a bit; I painted and illustrated it here, on our website. Here's the link on our web page to check it out:

Click here to read Skip's essay Montana Hoppers: The Princess and the Brute...

Skip's latest books:

Top 12 Dry Flies for Trout Streams: How, When, and Where to Fish Them, is now available on Amazon as an ebook...check it out! Click on the links below to go to the information page on Top 12 Dry Flies (the link to Amazon is at the bottom of the page...)

Top 12 Dry Flies for Trout Streams: How, When, and Where to Fish Them

Top 12 Dry Flies for Trout Streams: How, When, and Where to Fish Them

Click here to get more information about

Top 12 Dry Flies for Trout Streams: How, When, and Where to Fish Them (the link to Amazon is at the bottom of the page)...

Top 12 Dry Flies for Trout Streams: How, When, and Where to Fish Them (the link to Amazon is at the bottom of the page)...

Top 12 Nymphs for Trout Streams: How, When, and Where to Fish Them, 2nd Edition, originally published as an e-book only, is now available on Amazon as a paperback...check it out! Click on the links below to go to the information page on Top 12 Nymphs (the link to Amazon is at the bottom of the page...)

Top 12 Nymphs for Trout Streams: How, When, and Where to Fish Them (2nd Edition)

Top 12 Nymphs for Trout Streams: How, When, and Where to Fish Them (2nd Edition)

Click here to get more information about

Top 12 Nymphs for Trout Streams: How, When, and Where to Fish Them (2nd Edition). . .

Top 12 Nymphs for Trout Streams: How, When, and Where to Fish Them (2nd Edition). . .

Click here to get more information about Skip's e-book,

500 Trout Streams...

500 Trout Streams...

Skip's latest paperback book:

365 Fly Fishing Tips for Trout, Bass, and Panfish

365 Fly Fishing Tips for Trout, Bass, and Panfish

Click here to get more information about Skip's latest book,

365 Tips for Trout, Bass, and Panfish...

365 Tips for Trout, Bass, and Panfish...

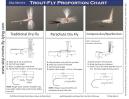

Print Skip's chart for FREE:

Skip Morris's Trout-Fly Proportion Chart

Go to Skip Morris's Trout Fly Proportion Chart

Skip's Predator is available to buy...

Skip's ultra-popular Predator—a hit fly for bluegills and other panfishes and largemouth bass (also catches smallmouth bass and trout)—is being tied commercially by the Solitude Fly Company.

The Predator

CLICK HERE to learn more about or to purchase the Predator...

Learn to Tie Skip's Predator

Do you want to tie the Predator?

Tying the Predator

Skip shows you how to tie it on his YouTube Channel link, listed below:

CLICK HERE to see Skip's detailed video on how to tie the Predator...